A Glimpse of the Afghan past

Before the drones, cluster bombs and cruise missiles, before the Mujahedeen and the Taliban and suicide bombers, before the proxy war between the USSR and the USA, Afghanistan was a pleasant and peaceful place in the seventies: just for a while! Afghanistan, which had remained neutral during the Cold War under the astute leadership of King Zahir Shah, had become the next victim of super-power geo-politics after his

ouster by his cousin, Mohamed Daoud. This unfortunate ancient land, lying in the crossroads of Asia on the ancient Silk Road, has seen great ancient civilizations as well as chaos and misery that continues to date. Prosperity and power was created in ancient times around cities like Bamian on the Silk Road, where muslin and spices from India were added to silk and porcelain from China to make the biggest trade route to the Mediterranean. But history moved and Afghanistan was left behind.

Ancient Buddhist history resonates with names and places from this war-torn country: Taxila, which became a Buddhist centre with an international university under Emperor Asoka Mauriya (273-232 B.C.) who first

unified most of India and a part of Afghanistan; King Kanishka (2nd A.C.) of the Kushan Empire who fostered Buddhism from his capital Purushaputra (Peshawar after the Moghuls); Gandhara (today the Swat Valley, the scene of much death and destruction) where some of the most exquisite Buddhist art and sculpture influenced by the Greek tradition flourished between the 1st-5th A.C.; Menander, the Greco-Bactrian king (2nd B.C.) referred to as King Milinda in the popular Buddhist treatise named Questions of King Milinda by Nagasena Thera. Much later, after the Islamic conquest of the 7th C., Mohamed of Ghanzi invaded India in the 11th A.C. and in the 16th A.C. the Afghan ruler Barbur conquered North India to establish the Moghul Empire and develop the efflorescence of North Indian culture which we greatly admire. Sadly, Westerners know Afghanistan only as a place of violence and terrorism which they must put down with maximum force.

By the time I started visiting Afghanistan during three consecutive years from 1975-1977, it had become a backwater that was generally ignored by the rest of the world. The invasions by rival British India and Russia to control this border state in the earlier centuries had lapsed and the rivalry of the Soviet Union and the United States to control it had not yet begun. I was the export manager for the Sri Lanka subsidiary of Unilever Ltd., the Anglo-Dutch consumer products multinational, selling soap and cooking fats in the Middle East with Afghanistan as one of our markets.

The Afghans

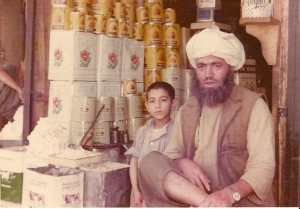

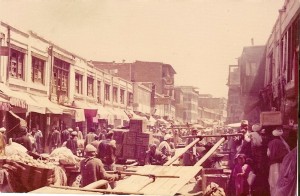

Afghans are tough, hardy and very independent people: otherwise they would not have survived in their harsh mountainous land and centuries of wars. They will react violently if offended but are generous and hospitable at other times. Two personal incidents etched this in my mind. On my first visit in 1975 I walked through the large, sprawling, dusty, incessantly noisy, seemingly chaotic Kabul bazaar. Dusty avenues were lined with little one room shops which sold a wide range of foodstuffs, cloth, medicines, pots and pans and other household items. It was teeming with activity as men and boys, dressed in their traditional loose garb, rushed along pushing carts or jostling each other. I spied a shop filled with large cans of cooking fat, the kind of product which we exported and I was selling in the country. The owner was a sturdy middle-aged man with a beard who was seated cross-legged on a table in the middle of his little shop. Instinctively, I snapped a picture of this with my camera and had a startling response. The burly fellow leapt from his perch and was on me with his rough hands strangling my neck. My friends from the sales agency yelled and extricated me. They explained to the angry

trader that I was a visitor to the country who was ignorant of their customs. The violent man became instantly apologetic. He went back to his perch and requested me to take a proper picture of himself and also to send him a copy. I did so and the picture is shown here.

Our sales agents were Watan Import Export Company. The sales manager of the company was the handsome, urbane and gentlemanly Akram Akbar who had been educated in the USA and was very proficient in English. Knowing I was fascinated by the countryside, he would take me by car on lengthy excursions to show me the sights. During each stay we visited Bamian, which was special for me. During one such visit we encountered a road block and took our place behind a line of about two dozen other cars. Checking out the problem, we saw

that the small bridge across a stream had been washed away by a sudden flash flood. I wanted to turn back but we were assured by the foreman of a gang of workers at the site that the bridge would be ready in a few hours. The stalwart fellows set about cutting the trees on the waters’ edge and throwing them across the stream. Then they poured earth over it and pounded it down. In about four hours the bridge was passable.

It was night when we re-passed the site on our return. Someone was waving our car to a stop: it was the same foreman and he wanted a ride home as we were going in the same direction. After some conversation between our friend and the new passenger, it was announced that we were invited to have dinner in the man’s house. We had to sadly decline the offer as it was very late and we needed to be in Kabul.

On one occasion, I made the road trip to Kabul without taking the small plane from Delhi. Peshawar, which had been incorporated in India by the British in 1879 after the Second Afghan War and then later

incorporated in Pakistan, was the starting point. Peshawar was a bustling industrial city which boasted a good international hotel, the Pearl Continental Hotel, where I stayed. Among its famous cottage industries were the manufacturers of exotic guns using very simple lathes and handcrafting techniques. They could reproduce rifles and shotguns as well as exotic fountain pen guns that looked like fountain pens but fired a lethal bullet at close quarters. Gun salesmen would come out of the shop and casually demonstrate a weapon to a potential customer by firing a shot in the air. There was no trace of the peaceful

Buddhist civilization of Gandhara and the ancient Kushans in this rough and bustling frontier city and its crowded bazaars, except at the Peshawar Museum which had many beautiful Gandhara Buddhist works of art.

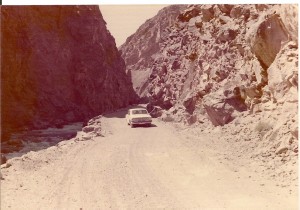

Kabul was only about 100 miles away. Our kindly and hospitable Afghan Sales Agent, Akram Akbar, met me at the Pakistan border post and we travelled by car to Kabul. The Pakistani border post was an unusual sight. Men in Afghanistan and the North West Frontier carry rifles of various vintages as part of their dress code, just as English country gentlemen would carry walking sticks as a fashion accessory. To enter the Immigration Office they were obliged to leave their weapons outside. So a long boundary wall was lined with the guns of passing

visitors. Beyond that was a No-Man’s land that went through the Khyber Pass that traverses 33 miles through the Hindu Kush Mountains, where the Pakistani Government had some authority but little control over the local tribes. Large signs by the Pakistani Government along the roadsides warned travellers

not to halt or disembark from their vehicles in this zone. It is mostly dusty desert with mud-built houses atop the barren hills looking like mini-forts. Family feuds were a constant in this region with vendettas going on for generations. The road to Kabul goes through Jalalabad and passes through bleak, mountainous country that is a characteristic of Afghanistan. The brown mountains were devoid of even a blade of grass.

The Afghan people have been self-reliant for thousands of years. They rely on their family and tribe, mistrusting foreign invaders and even the government in Kabul. They tougher and more resilient than any other I have encountered and they are willing to fight and die for their preservation. It is a quality they still demonstrate.

Afghan society

Though it was mostly an unsophisticated and simple society, Kabul had extensive bazaars and a vibrant trading class. It was famous for its dried fruit and nuts, which constituted the major exports, while various foodstuffs were imported from neighbouring countries. Money-changers in street shops were ready to change local currency into most international currencies. Importers went to these money-changers with sacks of local currency to buy dollars and then went to the Bank Melli in Kabul to open

Letters of Credit. Exporters shipped goods only to Karachi, from where Afghan clearing agents collected goods and loaded these on goods trains to Peshawar. From Peshawar, trucks carried the goods to towns in Afghanistan. It sounded complicated but I am not aware of any cargo that was lost in transit.

Despite its seedy appearance, Kabul boasted an Inter-Continental Hotel. The other high-class hotel was Kabul Hotel, looking more old fashioned and stately but a little seedy. The Inter-Continental Hotel had a Sri Lankan band playing in the dining hall and hotel guests danced to the crooning of a Sri Lankan girl. Wine was served and there was even a local wine on sale. The small middle class in the cities wore smart Western clothes and most spoke foreign languages.

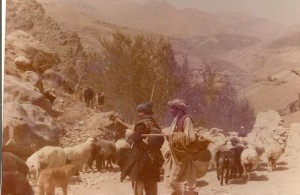

Afghanistan was a very poor country even then. Many parts of the city lacked sewage systems and a malodorous air greeted those who walked the side streets of the cities into which faecal matter from some household toilets flowed. In the countryside, most of the people were very small farmers or herdsmen. Nomadic families were on the move in spring, taking their flocks to higher ground, tents packed on camels, women and children often on horseback, even though the women were covered with the veil. Large and dangerous looking mastiff-type dogs ran alongside these caravans. The countryside was bereft of any vegetation except alongside snow-fed streams coming from the mountains where crops were grown on either side.

The countryside produced some of the sweetest fruits and dried fruit and nuts. While travelling by car, our hosts would obtain sweet melons and on arriving by a cool mountain stream would leave these in the icy waters to cool before cutting and serving

them. I have never tasted sweeter melons anywhere else. The roadside eating places were memorable. One had a dining room set out on the roadside with a trellised roof covered with grape vines, with large bunches of grapes hanging above our heads. They usually served tandoori nan bread. The bakers flattened lumps of dough and pasted it on the inside of a large rough clay oven. When the flat bread was done it fell on to the coals and ash at the bottom from where it was picked up, the ash dusted off and it was handed to the customer.

Bamiyan and Band-i-Amir

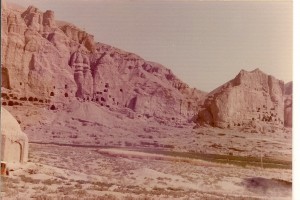

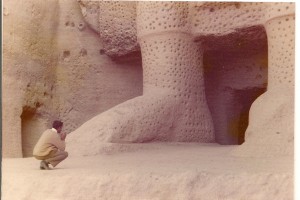

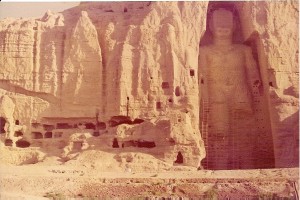

The lush Bamiyan Valley surrounded by mountain ranges was an important midway hub on the Silk Route which connected China with the Roman Empire. The gigantic statues of Sakyamuni Buddha[1] are estimated to been built here around the 4th-5th A.C. No records exist of the builders of these monuments. They were an imposing sight, one statue 175 feet tall and the

other about 120 feet, both carved into the sandstone rock of the mountain. To the caravans coming on the Silk Road, that were often preyed upon by marauding bandits, the distant sight of these giant Buddha images signified an oasis of peace and tranquillity where they could rest safely or do business.

When I saw these in the nineteen seventies they had lost their once painted surface, though traces of frescoes could be seen in the mountain walls into which these were carved. Parts of the statues had been deliberately destroyed by the invading armies of Ghengiz Khan in the 13th A.C., long before the Taliban completed their atrocities in 2001. During our visits the Indian Archaeological Department was carrying out some restoration work and scaffoldings had been set up. The mountain face was pocked with thousands of blackened caves where thousands of monks had once meditated. They too had met a violent end and their frugal possessions burnt. Such was the fate of many Buddhist places in the past which offered non-violence to adherents of violent religious faiths in the certain belief that the Laws of Karma would eventually balance out these rights and wrongs.

Steep stepped passages inside the mountain enabled us to climb to the top of the statues and from there to the head of the Buddha image. This would have enabled people to do their maintenance work in ancient times. When we climbed to the top

and I was on the point of stepping on the head of the Buddha image, my office colleague from Sri Lanka shouted to me against committing such a sacrilege.

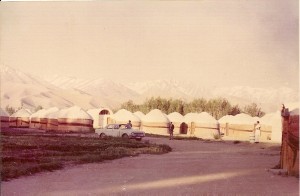

We lodged in a picturesque hotel consisting of round Mongolian-style tents which were equipped with modern conveniences. The local Hazara people had little knowledge of the history of the place but preserved it as tourism brought in revenue. There was always a sprinkling of Japanese tourists who had come to admire and venerate the statues which were symbols of Mahayana Buddhism. Some of them prayed aloud near the statues.

From Bamiyan Valley we travelled on another dirt road, climbing over 10,000 feet to reach the Band-i-Amir lakes. Here, amidst the barren mountains, aquamarine blue lakes with pristine clear and clean water nestle like giant cups in the midst of nowhere. At the jagged edges of these giant cups, small streams of water flow down to the bottom where millers have set up water wheels to move grinding stones for flour milling. After we enjoyed a snack of local sheep’s milk yoghurt and bees’ honey, we met a group of small boys who sold us fossilized sea shells from the mountains which seventy million years ago (Upper Cretaceous Period) had been under the ocean. I still treasure these.

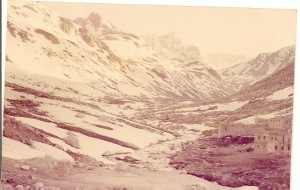

Another interesting site was the Salang Tunnel which pierces the Hindu Hush Mountains north of Kabul at an elevation of about 10,000 feet to give road access to the north of the country. The Salang Valley was the traditional route to the north but till the Soviet Union built this tunnel in 1964 the road over the mountains was arduous. When we visited the site in spring the whole region was still covered in snow. The tunnel is 2.6 kilometres long but can be dangerous in winter due to frequent avalanches that can block the exits. In those times snow covered even the mountains surrounding Kabul in spring though it is uncertain that this happens in this era of climate change.

The beguiling beauty of Afghanistan and its people in the seventies kept me for ten days in that location on each business visit, while I only spent three days at the most in my business visits to Middle East destinations. This caught the attention of the British Chairman of our Unilever Company and he queried: “Kenneth, do you really need to spend ten days at a time in Afghanistan?” I responded tongue in cheek: “Yes, three days for business and seven days for sight-seeing. After all, I am the marketing manager and I need to get a feel of the country for our business.” “You are quite right!” said this sensible man.

Kenneth Abeywickrama

November 2010.

All copyrights to this article are reserved. Reproduction will be allowed after approval of a request for publication.

[1] Statues of the Buddha are not worshipped in Buddhism as the Buddha was neither a god nor a saint but a human being who was an Enlightened One. Buddha statues were prohibited in Sakyamuni Buddha’s lifetime. They are since intended to be a focus to help meditation or recite prayers for the well-being of mankind, animals and gods. Worshippers do not ask personal favours of the Buddha, as in other religions. A person’s fortunes are determined by past karma.

| M.A. Akbar makbar3660@msn.com 173.169.125.241 |

Kenneth,

|