Sierra Leone: An African Tragedy

Diamonds have brought out sometimes the best and more often the worst in Man. This illustrates the history of Sierra Leone in recent decades. Sierra Leone (literally, the Lion Mountain, area 71,740 sq. km, population 4.75 million as per 1995 estimate), is physically extraordinarily beautiful, politically chaotic, and the mass of the people are desperate for survival. The lush tropical vegetation, fertile soils and the plentiful mineral and water resources would have made this country a paradise under normal circumstances. But according to the Annual UN Human Development Reports, Sierra Leone is the worst country in the world for people to live in. But that doesn’t tell the real story of how this came about and what role outsiders have played in this tragedy.

Our small team of UNIDO consultants arrived by different flights into Freetown on 29 March 1996, on the very day that His Excellency Ahmad Tejan Kabbah was inaugurated as President of Sierra Leone in the hope of ending a long period of chaos and lack of governing authority and establishing some form of legitimate elected government. It was evident on landing in the tiny airport that this was not a holiday destination. The airport exit was thronged with ill-clad young men who aggressively confronted passengers and offered to lead them to the city about 25 miles away across a lagoon. Since there were no information, tourist or taxi booths as in other airports, we submitted to a gang of four who had already seized our bags and led us to a battered car which transported us to a jetty from where an ancient ferry, that had seen grander days in Britain half a century ago, carried us twenty miles across a lagoon to the city of Freetown. I must admit that our four guides solicitously protected our baggage and then led us to a taxi to get to the hotel and were pleased with the payment offered.

Sierra Leone was not a governable country and the writ of the government did not extend beyond the capital city at the time and even this was often a nominal authority. The curse of diamonds compounded the misery of this unfortunate country: lots of diamonds that could be obtained in many places by crude surface mining methods. Breakaway sections of the army and other lawless groups occupied these regions to mine for diamonds, while South African diamond dealers arrived in bush planes to buy these. The fortunes made from these financed weapons and armies to sideline or even take over the government at the centre. Much of the countryside was controlled by the Revolutionary United Front at the time, the ragtag army of bandits led by ex-army corporal, Foday Sankoh, who was allied to the equally obnoxious Charles Taylor who ruled neighbouring Liberia. These terrorist groups committed unspeakable cruelties against local villagers, killing and destroying villages, and cutting off the limbs of young people and even children, to terrify people to submission to their authority.

Tribalism

Sierra Leone was a very troubled nation which has seen a succession of military coups and civil wars, interspersed occasionally with elected governments, ever since the British granted self-government to the colony in Freetown and the larger protectorate surrounding it in 1961. Its people could hardly remember a period of prolonged peace and development. As was the pattern in Africa, this artificial nation was created by the British who established Freetown in 1787 as a settlement for freed slaves and then extended their control over the surrounding region by making it a protectorate which was ruled regionally by the local tribal chiefs. So it became a nation of 18 tribes, of whom the biggest are the Temne and the Mende, and a smaller population of Krio elites in Freetown, the descendants of the liberated British slaves from the West Indies. By a strange twist of circumstances, the descendents of slaves from the West had become a superior social class to the descendents of free people in their own country.

However, apart from the Christian missionaries who founded good schools that created a small elite professional class, chiefly from among the Krio, the British government did little to improve the condition of the local population or develop its economy beyond creating the basis for British commercial enterprises exporting diamonds, bauxite, rutile, gold, cocoa and coffee. One great testament to the work of the Christian Missionary Society of Britain is the Fourah Bay College, founded in 1827, the oldest western-style university in West Africa.

Tribalism is the basis of much of the social mores and woes of an African state. Tribal settlements do not always fit into clear geographical boundaries and tribal customs do not conform to modern cultural practices. Propagandists for traditional culture throughout Africa loudly praise the security offered by the tribe to its members but this kind of primitive organization does not mesh with the requirements of a modern society and the tensions caused by tribal loyalties is a major cause of the perpetual conflict and bloodshed in Africa. Lands in Sierra Leone, outside the capital Freetown, are legally owned by tribal chiefs and these are not marketable. People wanting land for business or farming must lease it from the chief, unless they have sufficient military might to seize it by force.

We had an insight into the nature of tribalism when we visited the small national museum in Freetown. Such cultural institutions had been officially neglected by governments after the British left but this museum was being maintained because of the dedication and resourcefulness of an elderly South African woman who was its director. She was a small and frail woman of great scholarship in local lore who had made this country her home. Finding an interested audience in us, she personally guided us through the museum. Most of the exhibits were frightful looking tribal costumes used on ceremonial occasions. She told us that all her staff belonged to some tribe. Each tribal group had its own secret societies and had their initiation ceremonies, separately for men and women. These were so secret that they would not reveal these even to her for fear of violent reprisals. But it was known that these ceremonies involved living together for several weeks in the jungles where elders dressed in fearsome costumes and masks taught them ancient social practices and guidelines for survival through ritual dances, songs and forms of physical torture and mutilation.

In-house bandits

The UN Chief Security Officer was the first to meet us at the Hotel Bintumani. He warned us that rebel attacks on the city were a possibility we had to take account of. In such an eventuality we should all gather in the adjoining beach from where arrangements would be made to airlift UN staff out of the country. There was plenty of evidence of the pervasive chaos in that corner of the world: there were about 50 UN staffers who were brought for their safety from neighbouring Liberia and housed in the hotel next to ours. Part of our work plan involved visiting two interior cities: Bo and Magburaka. He advised us against such visits to the interior: bandits not only robbed travellers, they had no compunction against killing foreigners.

With all these precautions, we were still ill-prepared for our own in-house bandits. Because of the unstable conditions in the country, our UN agency decided to send our living allowances and project expenses (which I, as Team Leader, would allocate) through the local UNDP office instead of crediting our bank accounts. So on the first working day our team gathered at the local UN offices at Siaka Stevens Street and met the Programme Officer, whose job was to look after the welfare of UN personnel working on UN projects. In the UN hierarchy, he is but a lowly clerk but that was not how he presented himself to us. The cash was in his hands and we were the recipients and that is the advantage this man wanted to demonstrate. In a quite unfriendly manner he asked us to come the next day.

We came the next day. Having worked quite often in Africa, I could read his signals but we agreed that bribing UNDP staff to get our dues was too outrageous. The next day, after some further delay, we were sent to the Accountant who was also always too busy. By the end of the day, checks were issued to us together with what seemed good advice. Since the security situation in the country was bad, we should not keep large sums of cash in the hotel. He gave us letters of recommendation addressed to the local Commercial Bank and told us to open accounts in the bank for safety.

Opening new accounts was easy. It was a large bank in a large building. A pleasant young lady in the bank opened our new accounts with alacrity and gave us check books. Whenever we visited the bank, either for deposits or withdrawals, this helpful clerk would come rushing from her desk to help us. At the end of the month, after making a new deposit, I sought a statement of the account. She went away and came back to state that the computers were not working and a statement could not be printed. This raised a red flag. I came back the next day with my colleagues and we asked for our bank statements. Again the smiles and the friendliness, and another excuse came out as to why such a statement could not be produced. I had learnt the name of the British General Manager of the bank and told her (quite untruthfully) that he was a friend and I would go up to his office and get the statements. At this, the clerk went back and came a little later with the statements. Glancing through the statements, we noted that each of us had been recorded for three or four cash withdrawals amounting to about US$600 of which we had no knowledge. Again we brandished the name of the General Manager and said we would meet him and draw his attention to the errors. At this the lady rushed back and came with a set of corrected statements. We promptly asked for the closure of our accounts. It was safer to keep the monies on our person than trust it to a Sierra Leone bank.

That was not the end of our woes with the UNDP office. We needed and car and a chauffeur for our work. Money had been sent for these purposes and again we went to the UN Programme Officer for his assistance. He was now much more cooperative. He promised to arrange a car by the next day. The next day he said we were lucky he was able to obtain the vehicle we needed at a cost of only US$60 a day. But when we went back to our offices at the Ministry of Industry, our helpful liaison officer, Joseph W.A. Jackson, was outraged. He said that it was double the going price for a hired vehicle. He would produce a dozen people who would provide a better rate. By evening we had a dozen car owners bidding for our business for US$25-30 per day. I chose one who had a fairly new Mercedes for US$30 per day.

We went back the next day to tell the Programme Officer that we had located a car for half the cost. His newly acquired friendly demeanour soured and he told us abruptly: “If you think you got a good deal, take it.” We took the driver and his service was excellent. After the first week, I gave him the invoice to collect his fee from the Programme Officer. He came back and told us that the Officer had abused him and chased him away. This was becoming complicated. We sent him again the next day with our request that he be paid. He came back to say that he was not going to be paid and therefore he could not afford to work for us. So we went back to the Programme Officer. He triumphantly told us that such things had to be organised with his guidance as we were foreigners. We would have our car and it would cost US$60 per day. There was no point fighting the system. We had our own work to complete on a tight schedule. There was no higher authority that would listen to our complaints, even if we could meet the local UN Resident Representative who was never in his office when we tried to reach him.

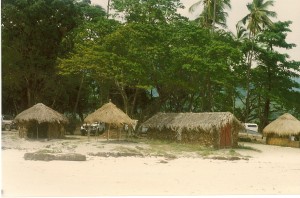

The car was a large and very old Mercedes and the chauffeur was a stalwart fellow of imposing size. He proved to be a very decent companion. He claimed that his brother was the army commander and that he would be our driver and bodyguard. During week-ends, he took us sight-seeing and introduced us to a lovely private beach in a little village by the sea where the local village youth association catered to paying guests and provided fresh sea food grilled in our presence in their beach huts. It was then that he told us: “Sir, don’t think I am paid $60 by the UN Programme Manager. I only get half the amount and he keeps the rest.”

The homeless and the Good Samaritans

While the international community, which comprises the power elite of the West, invaded and bombarded Serbia, Iraq and Afghanistan, with and without UN approval, it sought to ignore the far greater tragedies in Africa in Ruwanda, Congo, Sierra Leone and other African states when it was most needed. Instead, it sent its favoured therapists, the Western NGOs and their aid agencies. Freetown, a small city of half a million people, was now bursting at the seams with one million refugees escaping from the horrors of the countryside. Every family I came to know in the city had around two dozen relatives who had fled their homes in the countryside.

Hundreds of displaced young men slept on the beaches at night. A morning walk on the beach near the hotel was not recommended. During the first few days, before we became wiser, a morning walk on the beach drew swarms of ragged young men demanding money, screaming “Pappy, Pappy, give money, give money.” It was wise to carry some loose cash to avoid being beaten up. It was wiser to avoid the beach altogether. Young girls dressed in tight black lace sequinned dresses roamed the streets near Hotel Bintumani where we stayed and accosted hotel guests who came out. We usually took a car to get to the excellent Lebanese restaurants by the lagoon where we usually dined but one evening my Indian Sikh colleague (always wearing his turban) suggested we walk there for the exercise. We brushed aside the women trying to accost us but two drunken women were determined to get us. They refused to leave us and when we started jogging to outrun them, they continued running behind us screaming “Bombay Man, Bombay Man, I love you!” As we neared the restaurant, the waiters who saw our plight came out with broomsticks to chase the women away.

Sierra Leone was a dying society and was attracting the usual vultures. While the homeless refugees suffered, the three tourist hotels by the beach were fully occupied by foreigners from Western NGOs, aid agencies, diamond buyers, and others looking for fortunes or for trouble. Quite a number of the men were comforting attractive young refugee women with real love by lodging them in their hotel rooms, sometimes with little children. It was difficult to find out what these people were doing to save the refugees. One new foreign business investment was hugely successful. Young adventurers from Europe had set up shabby night clubs beside the beach road in makeshift buildings. By nightfall these were blaring loud music and crowded with foreigners, UN peacekeepers and young women trying to earn a living.

President Tejan Kabbah’s government had recruited some of the best public officers I have met in Africa. Many of them had fled the country during the turmoil but returned determined to build their country. Abdul Thoru Bangura, the Minister of Trade/Industry & State Enterprises, and his Permanent Secretary, T.M. Kargbo, whom we worked with, were brilliant and sincere men. So was Steve Swaray, Governor of the Central Bank. Clearly, the government had to be empowered to get the public service working as the Treasury did not have the resources even to pay the public servants. This was the pre-requisite for investment and economic development. So the biggest of the Good Samaritans, the World Bank and the IMF, had arrived to guide the country.

The World Bank Privatisation Programme for Sierra Leone was the pre-condition for IMF financial assistance to this bankrupt state which was trying to get on its feet. Without external financial assistance this country had no hope of survival. The major source of tax revenue, diamonds, was lost as the rebel groups controlled the diamond fields and the two companies that had the contract to legally mine had left the country. The maintenance and improvement of the national infrastructure was essential for the business sector to create the jobs which would make for social stability. But none of this was possible unless the country was freed from the rebel groups which controlled over 90% of the country and made all life and work insecure. The Nigerian troops in the country to control the rebels were unable to complete this task (it was only done by UN and British forces in 2002).

After much haggling, the World Bank and the IMF committed to lend comparatively modest sums to tide over the period with the caveat: 42 major public enterprises, including utilities, must be privatized within a strict time schedule. To do this, the Bank funded the small Public Enterprise Reform and Divestiture Commission, as they did all over Africa and Asia.

Our team paid a courtesy call on the Resident Representative of the local IMF office, Mr. Salaheddine Khenissi. He was an aristocratic personality of Iranian origin with the languid manner of those born to ease and comfort. He graciously waved us to his elegantly furnished sitting area. A valet brought in cookies and tea in a silver tea service. His world of Oriental luxury was far removed from the surrounding country. We told him that our mission was to get the privatization programme moving again. It was simple, very simple, he said with insouciance. He took out a magazine article and gave it to us. He said it was authored by the son of Milton Friedman, the right-wing US ideologue, and it contained the simple answer. The business enterprises of these poor countries were of no interest to a good international investor. The solution was to combine all leading public business enterprises into one conglomerate and offer it to a single foreign (read Western) investor. The new owner would dismantle and sell off the assets of the failing businesses and use these resources to develop the few viable ones. We left after thanking him for his valuable insights and his paper.

The Bank reform proposals envisaged the sales of public enterprises to Western corporations and Investment Seminars were arranged in London and Frankfurt. But there were no takers and, hence, there were no privatizations. Then the IMF tranches (as the instalment payments are called) stopped: No privatization, No loan money! That is when our team from the UN Industrial Development Organization was invited by the government to make a fresh proposal.

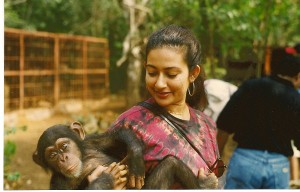

It was clear to us as rational people that no Western corporation would invest in such a war-torn and chaotic country. So to the annoyance of a World Bank team of experts, who clearly resented our presence, who were making their critical review report on the failures of the government from the comfort of their luxury hotel suites, we started a dialogue with local business people using the local Chamber of Commerce. Some of them were local, some were Lebanese, a few were South Asian, but all of them had a good track record of business success under trying conditions. One Ghanaian lady, Hanna Fola Thomas, was an outstanding business woman, owning 40 fishing trawlers, three oil tankers, a company making soap, a supermarket and other ventures[1]. These people indicated their readiness to buy the state enterprises, provided they were allowed to pay for the purchases in instalments over 6-10 years.

This became our key recommendation and caused immense enthusiasm within the government. The presentation of our report was held in the Central Bank auditorium and was attended by four senior cabinet ministers and the entire finance committee of the parliament. My presentation of one hour was shown on national TV throughout the day during the news hour. When I left the country the next day, I was a celebrity. At the airport, the Chief of Customs recognised me and loudly told his staff and others around him: “This gentleman is a true friend of Sierra Leone. We don’t need to check his bags.”

The story does not have a happy ending. The following year, 1997, the army overthrew the government and chaos reigned again. The ECOMOG troops, mainly the Nigerian peacekeepers, restored the government again in 1998. In 1999 the Liberian troops of Charles Taylor invaded Freetown and established Foday Sankoh, the terrorist leader. The ECOMOG troops again defeated the terrorists and captured Foday Sankoh. But instead of getting rid of the terrorists, the Western powers demanded peace with the terrorists and power sharing. Fodah Sanko became Vice-President and was given control of the diamond mines. In 2000 Foday Sanko and his terrorists again overthrew the government and occupied Freetown. In 2002 the terrorists were finally defeated by British and UN forces and Foday Sanko died in custody in 2003. Tejan Kabbah was re-elected president again in 2002 and 2004.

There is a moral to this story. No government should tolerate or compromise with terrorists on its own soil who wage war against the government and the civilian population with widespread brutality. Western powers are fond of demanding peace talks and compromises with terrorists in developing countries (Sri Lanka being a prime example) while they themselves are engaged in anti-terrorist wars half–way around the globe.

Kenneth Abeywickrama

18 December 2010.

[1] Her top managers were all Sri Lankans. She told me that when she wanted a manager she flew to Colombo to recruit one. She also had two small helicopters parked in front of her office in case of a need to flee the city.